A Commentary on Strange Fruit: Occasion of Composition and Dissemination

Tafsīr, Part One of Three

And the parable of an evil word is that of an evil tree, uprooted from the earth, having no stability (Qur’an 14:26)

Southern trees bear strange fruit

Blood on the leaves and blood at the root

Black bodies swinging in the southern breeze

Strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees

Pastoral scene of the gallant south

The bulging eyes and the twisted mouth

Scent of magnolias, sweet and fresh

Then the sudden smell of burning flesh

Here is fruit for the crows to pluck

For the rain to gather, for the wind to suck

For the sun to rot, for the trees to drop

Here is a strange and bitter crop

-“Strange Fruit,” performed by Billie Holiday and composed by Abel Meerepol

Here is a story told in lyric and song. It was crafted to reveal the brutal consequences of race. It moves us from the abstractions of race to the grounding realities of a specific people, time, and place.

“Strange Fruit” is a song that somberly captures the horrific violence committed against Black life in the United States in the early twentieth century and continues in new forms in the present. Like the bending branches of a tree heavy with fruit, the weight of this song’s words bore heavily upon those who heard it. The “strange fruit” of this song, however, was not some lifegiving culmination, but rather the dead Black bodies of the lynched strung from trees and swaying in the breeze. Sung in an incisively unhurried and unforgiving way, Black jazz singer Billie Holiday set this song forcefully before the averted eyes and muffled ears of the American public. Her commitment to perform the song turned the spotlight onto the horrors of anti-Black lynching in the United States. The song and its subject offer a striking contrast. The invoked lynching tree embodies the “evil tree” (shajara khabītha) likened to an “evil word” (kalima khabītha) – words sown by white supremacy – of which the Qur’an cautions us: And the parable of an evil word is that of an evil tree, uprooted from the earth, having no stability (Q. 14:26). In contrast, Holiday draws before our consciousness a series of good words - like the alluded kalima ṭayyiba (Q. 14:24) or “good word” invoked two verses before – aimed at revealing and challenging the anti-Black violence that underwrites modern structural racism.

In short time, “Strange Fruit” became the haunting anthem for those subjected to the terrors of lynching. The song’s spare lyrics, split across three stanzas, work multivalently, sounding as a dirge for the senseless dead, a lamentation for the living, an indictment of its perpetrators, a rejoinder to the amassed and complicit onlookers, a cry against the violence coursing through America’s veins, as well as a plaintive call to witness and respond.

The Occasion of Composition

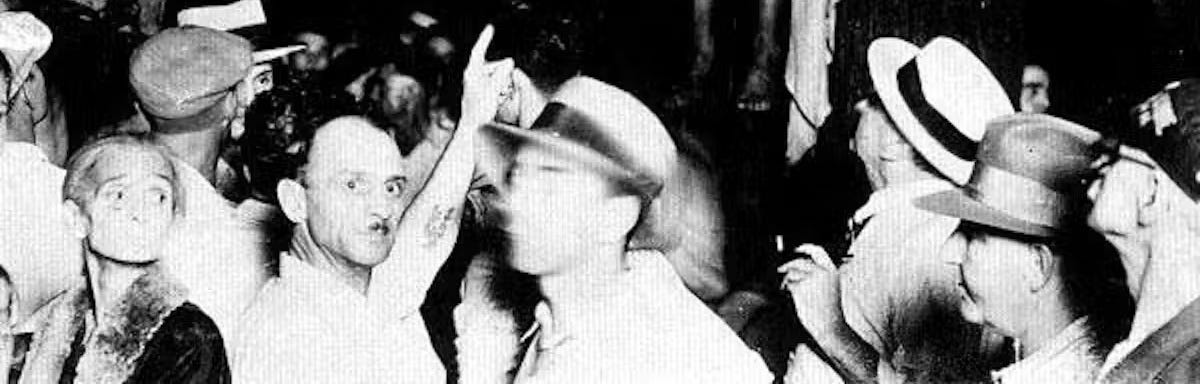

The occasion (or sabab) for the song’s initial composition lies in poetry. Abel Meeropol, under the pen name Lewis Allan, first published it under the title “Bitter Fruit” in January 1937 in The New York Teacher.1 Seven years prior on August 7, 1930 two young Black men, J. Thomas Shipp and Abraham S. Smith, were arrested on spurious allegations of robbery, rape, and murder in Marion, Indiana. Hours after their imprisonment several thousand furious white residents descended upon the Grant Country Jail and overwhelmed the sheriff and his men. The mob seized Shipp and Smith and lynched them.2 Their bodies were strung from the branches of a stately maple in the Courthouse Square. The grisly photograph of their bloodied bodies hanging above a crowd of placid white faces would eventually appear in The Crisis, a magazine of the NAACP. This haunting image likely inspired Meerepol to pen this poem.3

It is not insignificant that Meeropol was a Jewish American political activist. As Black liberation theologian James Cone remarks, “It was fitting for a Jew to write this great protest song about ‘burning flesh’ because the burning of black bodies on the American landscape prefigured the burning bodies of Jews at Auschwitz and Buchenwald.”4 While deeply engaged with activism and the arts, Meerepol was an educator by day. For more than a decade and half he served as a high school teacher. Yet because of his political affinity for Communism, his politics were kept discretely separate from his teaching.5 It would be many decades later, close to the end of his life, when Meeropol would disclose his authorship of “Strange Fruit” to one of his former students, James Baldwin, that gifted craftsman of the word.6 Meeropol set his poem to music and had it performed on several occasions at a range of venues.

The Occasion of Dissemination

The power of “Strange Fruit,” however, did not ripen until it came under Billie Holiday’s expert artistry. In early 1939, two years after the poem’s publication, Holiday would perform “Strange Fruit” at Café Society in New York City. Located in Greenwich Village, the countercultural venue was the first integrated nightclub in the city.7 The song became part of her “nightly ritual” and accompanied her even after she left Café Society later that year.8 Wherever she performed, “Strange Fruit” followed. It became an indispensable part of her repertoire. It became a part of her. When she would perform in places like the Onyx Club on West 52nd Street in the early 1940s, we can imagine friends of hers, like a young Malcolm X, being struck by the poignancy of its lyrics, even if he was still at that time a troubled “Detroit Red” mired in drugs and darker dealings.9 The seeds of “Strange Fruit” would have been planted in his already incisive, but still forming mind. Indeed, the words of this song would sink deep roots in the hearts of so many who heard it.

John M. Carvalho, “‘Strange Fruit’: Music Between Violence and Death,” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism(2013), 111.

James H. Madison, A Lynching in the Heartland: Race and Memory in America (New York: Palgrave, 2001), 5-9.

James H. Madison, A Lynching in the Heartland: Race and Memory in America (New York: Palgrave, 2001), 113; David Margolick, Strange Fruit: Billie Holiday, Café Society, and an Early Cry for Civil Rights (Philadelphia: Running Press, 2000), 36-37; Dorian Lynskey, 33 Revolutions Per Minute: A History of Protest Songs, from Billie Holiday to Green Day (New York: HarperCollins, 2011), 6-7.

James H. Cone, The Cross and the Lynching Tree (Maryknoll: Orbis Books, 2011), 138.

David Margolick, Strange Fruit: Billie Holiday, Café Society, and an Early Cry for Civil Rights (Philadelphia: Running Press, 2000), 33; Dorian Lynskey, 33 Revolutions Per Minute: A History of Protest Songs, from Billie Holiday to Green Day (New York: HarperCollins, 2011), 7.

Robert Reid-Pharr, “Transcript: James Baldwin’s ‘Little Houses’ and Abel Meerepol’s ‘Strange Fruit,’” Sarah Parker Remond Centre, University College London, https://www.ucl.ac.uk/racism-racialisation/transcript-james-baldwins-little-houses-and-abel-meeropols-strange-fruit.

John M. Carvalho, “‘Strange Fruit’: Music Between Violence and Death,” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism(2013), 112.

David Margolick, Strange Fruit: Billie Holiday, Café Society, and an Early Cry for Civil Rights (Philadelphia: Running Press, 2000), 16, 83; John M. Carvalho, “‘Strange Fruit’: Music Between Violence and Death,” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism (2013), 113.

Malcolm X & Alex Haley, The Autobiography of Malcolm X (New York: Grove Press, Inc., 1965), 74, 111, 113, 126, 129-130.

Wow! I was reflecting on this song last week. I look forward to reading this.

Thanks for sharing the history and context of this powerful song, Martin.