After their initial meeting in October 1963, Yuri Kochiyama reminds us that she wrote Malcolm X right away, “Then every day for weeks, I looked in the mail for an answer. The months went on.”1

By that time in her life, Yuri had already become a deeply engaged Harlemite, connecting with other folks and participating and organizing when the need arose. Rest assured, the needs were many. As she had done in her previous place, she opened her home in the Manhattanville Housing Project on 125th Street to friends, visitors, and many others. As biographer Fujino relates, “The Kochiyama’s home, with its relentless flow of visitors, has been dubbed ‘Grand Central Station.’ Over the years, thousands of people - friends and strangers alike - have dropped by.”2 Yuri and her family were committed to building community. As Yuri herself describes, “First there were only a few people, but as more and more people heard about our open houses, we soon had 100 people in our small apartment.”3

Yuri recalls one especially notable gathering in the Kochiyama home:

We held many memorable community gatherings in our new home. One such gathering was to hear the words of the Freedom Riders, an interracial group of activists from all over the U.S. who boarded buses headed for the South in order to protest the practice of segregated public transportation. In 1961 several busloads of Freedom Riders from New York left for the South. Some of buses were overturned in Alabama and set on fire. So when the Freedom Riders returned to New York, we invited some of the activists to speak at our house gatherings.4

Encounters like this only served to deepen and grow Yuri’s political consciousness. It built naturally upon her experience as a Japanese American during World War II. During internment Yuri had been active through organizing and corresponding with fellow Japanese Americans, U.S. soldiers included. By the war’s end, she had developed a extensive network of connections. It was these connections that would help bring Malcolm X back into the orbit of her life.

In an oral history interview, Yuri relates:

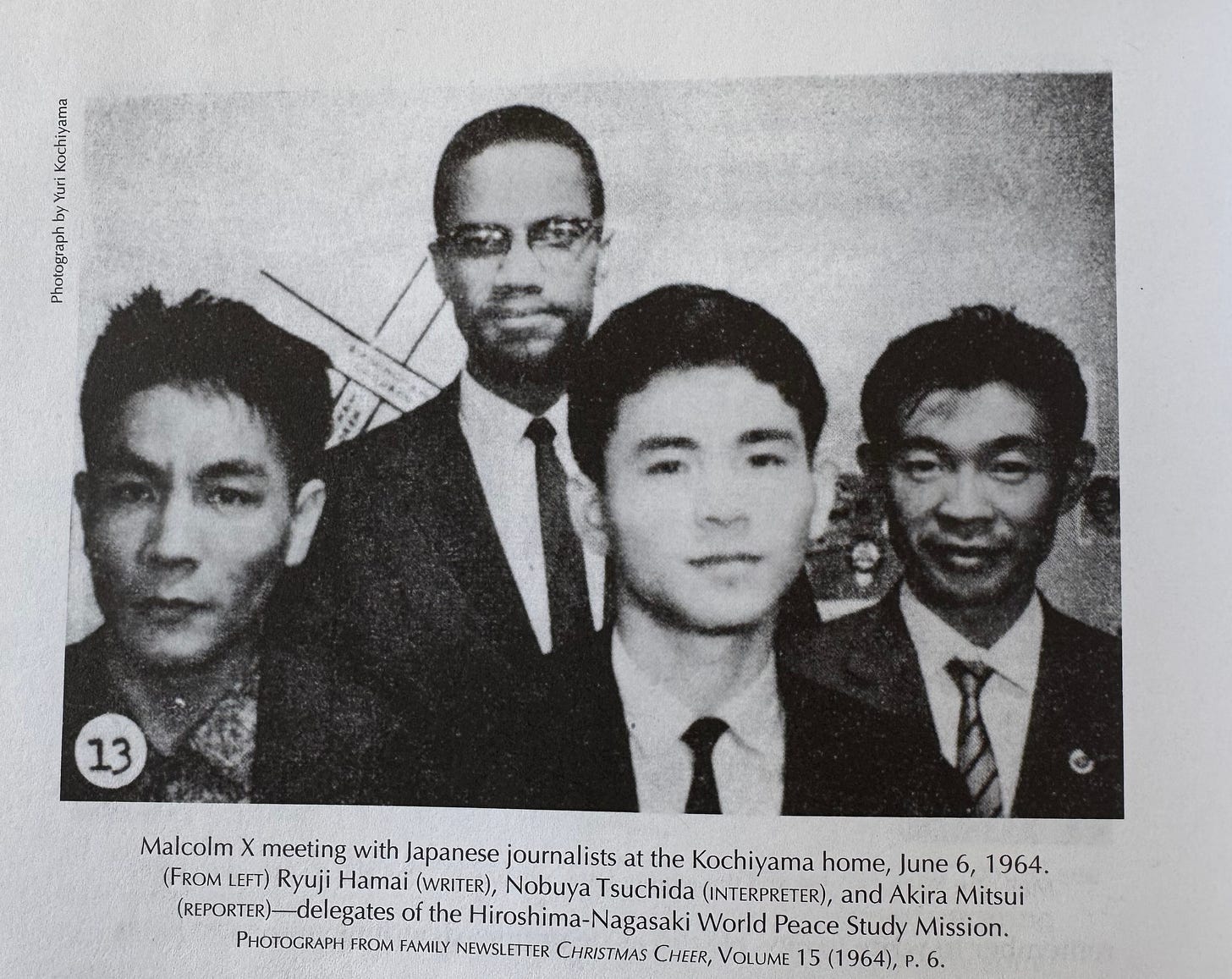

That January, in 1964, I got a call from the Hiroshima-Nagasaki World Peace Study Mission to help set up meetings with civil rights leaders in Harlem. The buildup of nuclear arms was increasing sharply and these Hiroshima-Nagasaki victims wanted to tell the world why it was necessary to stop. It was really a tour for nuclear disarmament. The Japanese wanted to visit Harlem and writers from that group wanted to meet Dick Gregory, James Baldwin, and Malcolm. Everybody wanted to meet Malcolm, if the truth were known, but he was so controversial that most groups kept their support quiet. Even though Malcolm didn’t answer my letter, I wrote to him about meeting with the atom-bombed Japanese writers... By June 6th, the day of the reception, we still hadn’t heard from Malcolm.

The three visiting members of the mission, known as hibakusha or “atomic bomb survivors,” were Kenmitsu Iwanaga, Akira Mitsui, and Ryuji Hamai. These writers, Yuri recounts, “wanted to meet Malcolm X more than any other person in America.”5

Yet, as the day drew near the prospect of arranging the desired meeting seemed increasingly unlikely. As Yuri writes:

We wrote months in advance to Malcolm at his 125th Street office, inviting him to meet with this Peace Mission, but we received no word. People told us he would never come. After all, he did not know us, and the time was dangerous for Malcolm. He had left the Nation of Islam only three months earlier. There were also rumors that Malcolm might be killed, but who would kill him? Who would benefit by his death? The Black movement activists felt the American power structure would benefit, not the Nation of Islam.6

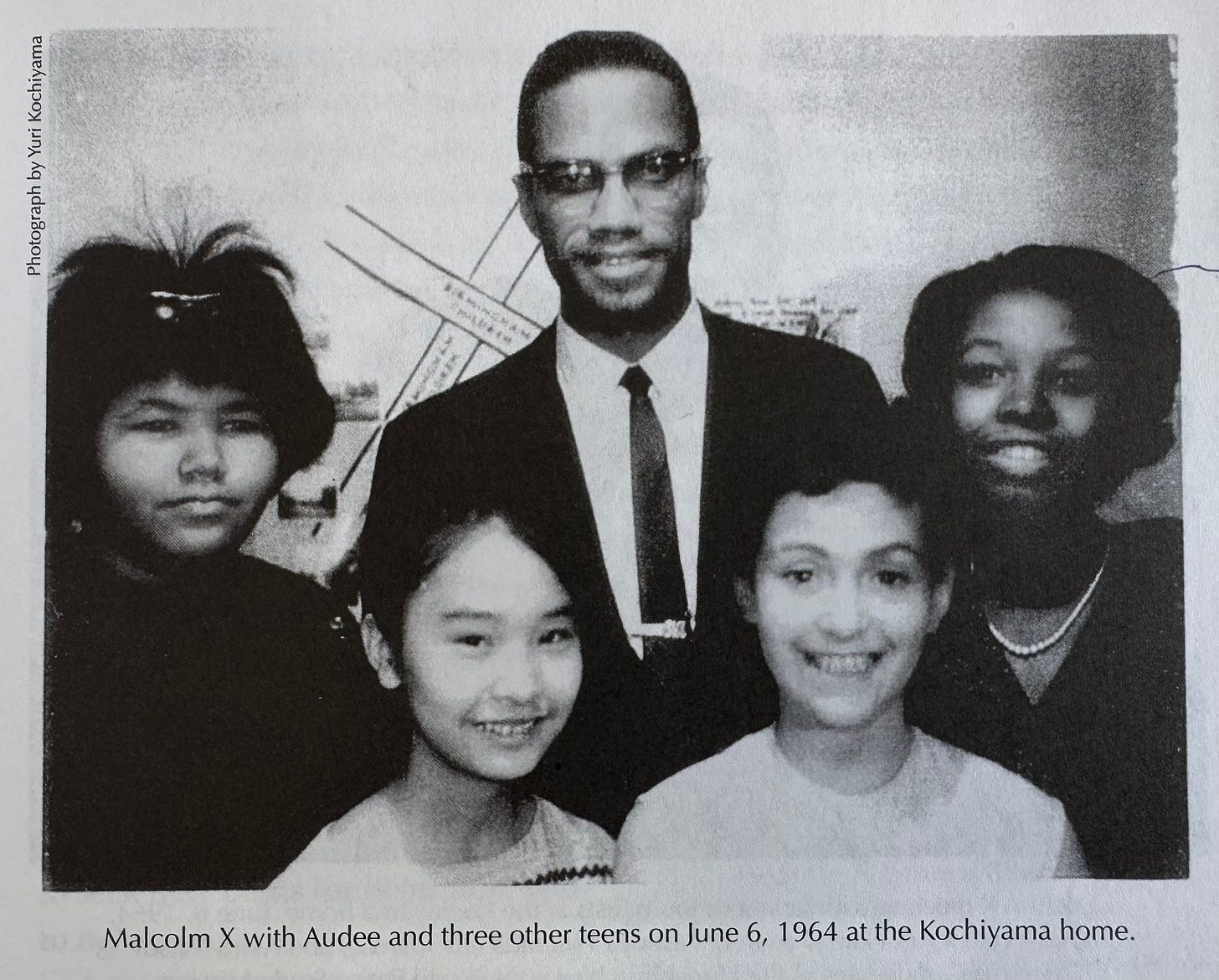

The day that Yuri and her family were scheduled to host the hibakushi or “atomic bomb survivors,” June 6, 1964, finally arrived. While the visitors toured Harlem that Saturday, the Kochiyamas still had heard nothing from Malcolm or his people. As the visitor’s tour drew to a close, many in the Harlem community had gathered in Yuri’s third floor apartment for a brief program with the writers.

At our place, where the reception was scheduled, we finally told the Japanese that the people they wanted to meet weren’t coming. In April, Malcolm had made the statement that he was going to leave the Nation of Islam and there had been threats on his life. Word was going around that he would be killed by the end of May, and we were into June. People had said he wouldn’t take a chance coming to a place where he didn’t know anyone.

Anyway the place was jammed. The Japanese said they’d meet the people who did come - black leaders and civil rights workers - and be as polite as they could be, and leave. But just as the program was about to begin and everybody was seated, we got this knock at the door and there was Malcolm. ‘I know what you are going to say,’ he said, ‘I didn’t write you. I’ll make up for it.’

He came in and saw this packed house and went around to every single person, black, white, Asian, and shook hands with everyone, asking their names. He practically electrified the rooms. Then the program began.

In Fujino’s biography of Yuri published more than two decades later, Yuri offers a complementary recollection of that day:

His appearance electrified the room. But our guests were also apprehensive: Would he be hostile to such an integrated audience? Would he treat the Whites poorly? He was nothing the people expected. There was no arrogance, no egocentricity, no hostility; instead he was gracious, warm, personable. We all noticed that he was as friendly to Whites as to Blacks. He shook hands with everyone within reach.7

In her own memoir, Passing It On, Yuri shares the most detailed account of that visit yet:

Everyone was curious to know if Malcolm was really going to come. Shortly after the program began, there was a knock on the door - and there was Malcolm. He had three security men with him, but they blended so well with the crowd that we were not aware Malcolm brought anyone with him. When we later checked the guest book, we saw that three MMI (Muslim Mosque Inc.) men did sign. Upon entering the house, Malcolm first said that he was sorry he hadn’t answered any of my letters to him; he did not have my address…

As he walked into the living room, people surged toward him, wanting to shake his hand. He was gracious with everyone. The living room, kitchen, and hallway were crowded. He shook hands with as many people he could reach out to. People were impressed with his warmth even before he began to talk.8

After this expansive round of greetings, Malcolm provided what the hibakusha had been eagerly hoping for. He shared with them all his words. Yuri recalls:

When Malcolm began to speak... you could hear a pin drop. Everyone was focused intensely on this charismatic speaker. The hibakushas asked that the translators not interfere with Malcolm’s rhythm once he started speaking… Malcolm said: ‘You were bombed and have physical scars. We too have been bombed and you saw some of the scars in our neighborhood. We are constantly hit by the bombs of racism.’ He candidly described the years he spent in prison and that it was while in prison that he became educated by reading everything he could get hold of. He kept reading even after lights were out by the dim glow of the hall light. He started with the dictionary, reading from A to Z. He loved history and had read a lot of Asian history. He explained that almost all of Asia had been colonized by Europeans except Japan. The only reason Japan wasn’t colonized was because Japan didn’t have resources that Europeans wanted. All over Southeast Asia, European and American imperialists were taking rubber and oil and other resources. But after World War II, Japan did provide valuable military bases for America, especially on the island of Okinawa. It was because Japan hadn’t been colonized that Japan was able to stay intact and become so strong until her defeat in World War II.9

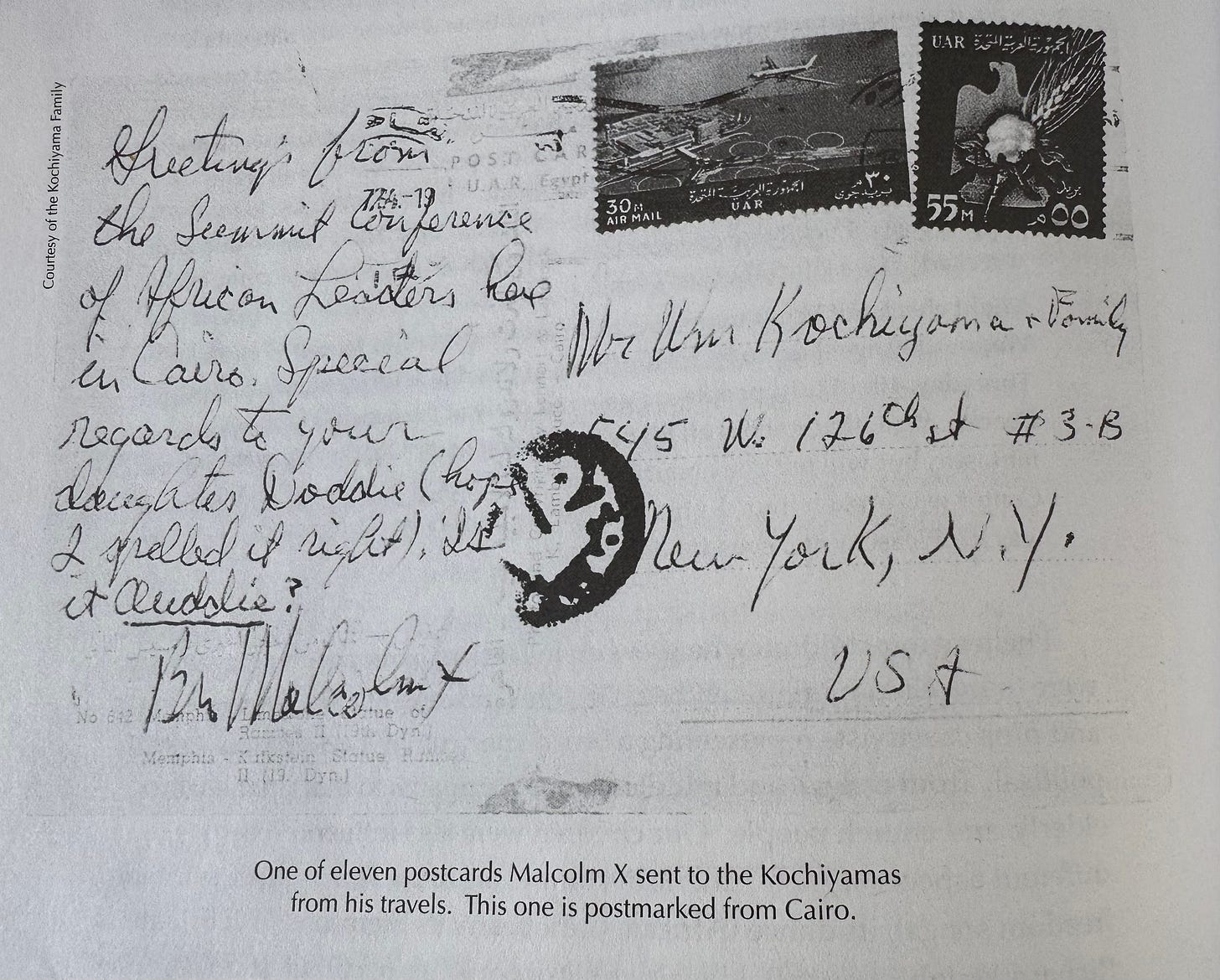

“A week later he left the country on a trip to Africa and the Middle East, and every few days we would receive a postcard from him...”10 In total, Yuri and her family would receive eleven postcards sent from the many places abroad that Malcolm visited. Those postcards are preserved today as part of the Yuri and Bill Kochiyama Papers, 1936-2003 archived at Columbia University. In one postcard, Malcolm writes: “I read all of your wonderful cards and letters of encouragement and I think you are the most beautiful family in Harlem.”11

In remembering these received messages, Yuri shares, “That so busy and important a person would take the time to write humbled me.”12 This, of course, was not the end of Malcolm’s influence on Yuri Kochiyama. In the days after the community gathering held at her Harlem home, she and her family would undertake an education in liberation deeply informed by Malcolm X.

Yuri Kochiyama, Fishmerchant’s Daughter: An Oral History, Vol. 2, ed. Arthur Tobier (New York: Community Documentation Workshop, 1982), 3.

Diane C. Fujino, The Revolutionary Life of Yuri Kochiyama: Heartbeat of Struggle (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2005), 94.

Fujino, Revolutionary Life, 95.

Yuri Kochiyama, Passing It On: A Memoir (Los Angeles: UCLA Asian American Studies Center Press, 2004), 47-48.

Kochiyama, Passing It On, 67.

Kochiyama, Passing It On, 67.

Fujino, Revolutionary Life, 140-141.

Kochiyama, Passing It On, 68-69.

Fujino, Revolutionary Life, 141.

Kochiyama, Fishmerchant’s Daughter, Vol. 2, 5.

Fujino, Revolutionary Life, 143.

Kochiyama, Fishmerchant’s Daughter, Vol. 2, 5.

Her snippets about how Malcolm interacted with people remind me of descriptions of the Prophet's character :)