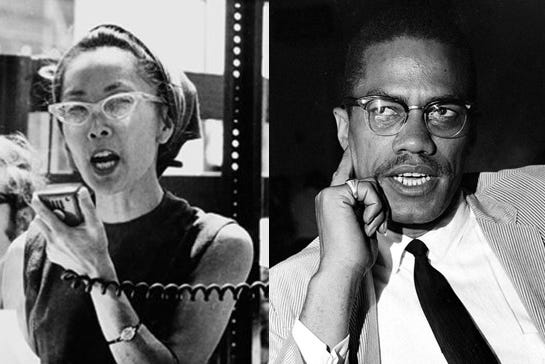

This year would have been Malcolm X’s 100th year in this world had he not been killed on February 21, 1965 on the stage of the Audubon Ballroom. While his time in this life was short (God had granted him only 39 years), he remains a guiding light for those of us still dwelling here on earth. Yuri Kochiyama, who knew Malcolm in his last days, remembers him similarly:

DuBois once wrote, “Throughout history, the powers of single Black men flash here and there like falling stars, and die sometimes before the world has rightly gauged their brightness. However, the many heroic Black men, and women, too (that American history books have buried), are rising out of the past... and their feats are being duplicated. Their deeds and their lives were not only momentary flashes like ‘falling stars’ but steadfast flows that lit the darkness of several centuries.” Malcolm was more than a “falling star” or an ordinary star which is sometimes visible and sometimes obscure. His life is a simile that can only be correlated with the most brilliant of all stars in the heavens, the North Star, for the North Star is the one star that does not change position or lose its bright intensity. It is the star that set the course for mariners; and that gave direction to slaves escaping bondage; and communicated men’s hope by allusion... Triumphantly illuminating today’s stark atmosphere, giving light and direction, invincible and inextinguishable, Malcolm is that North Star shining.1

In the years since his death, Malcolm has remained such a guide for many of us. For my part, I’ve tried my hand at weaving him into the fabric of my own words and continue to do so.

Malcolm, however, is by no means the sole star wheeling above illuminating the darkness. Other lights shine through the night sharing the sky, lights like his wife and partner in life Dr. Betty Shabazz, his indefatigable half-sister Ella Collins, the incisive James Baldwin, and the already named Yuri Kochiyama, inexhaustible in her own efforts, among so many others. As we navigate the challenges of the present - “today’s stark atmosphere” - by turning to the lights above, we would better served, I think, imagining Malcolm as but one part of a more brilliant stellar array - a constellation - shining boldly against the void and ready to guide us in trying times. How we each behold that constellation might vary (which stars to fix and how, the particular image to envision) but learning of those other luminaries set alongside Malcolm is certainly worth our time. In this essay and others to come (insha’Allah), I’ll do my best to trace out the constellation that I behold - one fixed and delineated by the prophetic spirit of the Islam tradition (even if the how of it might not be apparent at first). Think of this year, 2025, as a venture in stellar cartography where I’ll spend much of my time here (though not all) trying to set El Hajj Malik El Shabazz, our brother Malcolm X, into a constellation of other luminous lives. In fact, I’ll open with a series of pieces on Yuri Kochiyama, whose very words opened this essay.

Malcolm and Yuri were kindred spirits, committed to their communities and full of a seemingly relentless energy. They also happened to share a birthday, May 19. While Malcolm would have turned 100 this year, Yuri (who passed away in 2014) would have turned 104. Although only living a few years apart, they would not meet until late in Malcolm’s appointed span of life, October 16, 1963 to be precise. Moreover, each of them experienced life in this country in distinct, but equally racialized ways. As a Japanese American born in San Pedro, California, Yuri and her family were subject to excessive harassment and surveillance at the outbreak of World War II. Yuri was 20 when the US entered the war in the aftermath of Pearl Harbor. The troubles amassed soon after. Her father Seiichi Nakahara was arrested by the FBI and died after being denied proper medical attention during his imprisonment. Then, in the wake of his loss Yuri and rest of her family, along with 120,000 others, were interned by the US government simply for being of Japanese descent. Yuri was forcibly displaced from her home in California and shipped eastwards to Jerome, Arkansas, one of ten concentration camps set up across the country. Citizenship mattered for nothing as more than two-thirds of the imprisoned - men, women, and children - were themselves US citizens.

Malcolm, for his part, was among the estimated two million African Americans who partook in the Great Migration from the rural south to the urban north. He was born in midst of it in Omaha, Nebraska. His parents, Louise (Langdon) and Earl Little, however, continued to move Malcolm and the family northward over the years. Like so many others, they hoped to escape the terrors of the Jim Crow South in the opportunities enticingly proffered by the industrialized North. Instead they only found other forms of racial subjugation in the cities of the Midwest (Milwaukee and Lansing) and Northeast (Boston and New York) that awaited them. Like Yuri, Malcolm also lost his father. While his death was officially ruled a nighttime streetcar accident, other accounts claimed that Earl Little was killed by white supremacists in Lansing, Michigan. After all, the family had been targeted and harried by the Klu Klux Klan and the Black Legion during their northward journey.

All roads, however, seemingly lead to New York. Yuri’s and Malcolm’s lives would eventually intersect in the racial justice struggles of Harlem. Yuri would move to New York City with her husband Bill Kochiyama in order to reside in the city that Bill called home. After some time in Central Manhattan, their growing family (now two daughters and four sons) decided in 1960 to move into the Manhattanville Housing Projects on 125th Street. In short time Yuri was drawn into various local justice struggles through the efforts of on-the-ground groups like the Congress of Racial Equity (CORE), the Harlem Parents Committee, and others.

While all these encounters would prove formative, it was Yuri’s meeting with Malcolm X that would radically transform her into the committed social justice organizer that she would later become. Put another way, Malcolm was key to her ‘conscientization.’ Yuri’s recollection of her meeting with Malcolm has been captured in a variety of sources. In an oral history account entitled Fishmerchant’s Daughter she recalls:

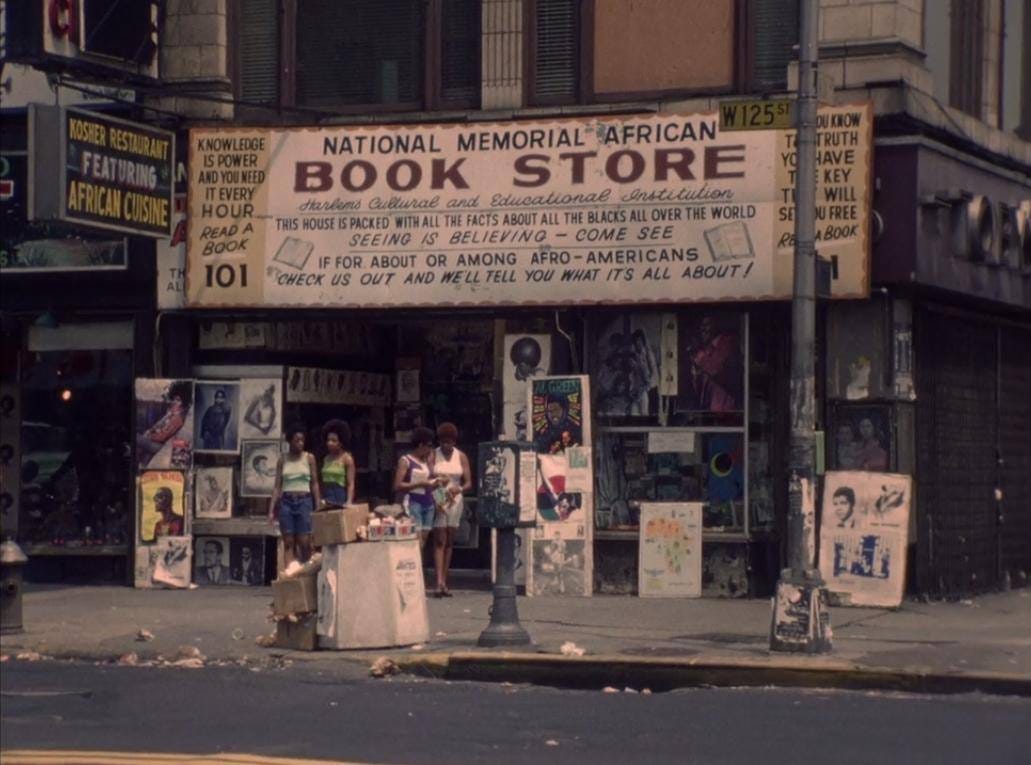

In Harlem, around the beginning of the 1960s, we started to see a lot of political people on the nights of our open house, people who had been in the South, fighting for civil rights, people who had seen the Cuban revolution. What they told us opened new doors for us. We weren’t involved yet. Mostly we were taking it in: watching the demonstrations on television, and reading about it in the newspapers. But what they said stayed with us. Then it was 1963. All of a sudden political activities were rampant in New York. Harlem was full of street-corner orators, including Malcolm. Malcolm used the corner on the same side of the street as Micheaux’s Liberation Bookstore on 125th and Seventh Avenue. The street-corner speakers drew crowds everywhere. If you were like me, you were stirred.2

{Point of clarification: Yuri appears to accidentally transpose two different famous Harlem bookstores. Lewis H. Michaux owned and ran the National Memorial African Book Store at 125th Street and 7th Avenue [Adam Clayton Powell Jr. Boulevard] from 1932 to 1974, which Malcolm X frequented. Liberation Bookstore, which Ulna Mulzac established later in 1967, was at Lenox Avenue [Malcolm X Boulevard] and 131st Street “just four blocks south of ‘speakers corner,’ where radical thinkers from Marcus Garvey to Malcolm X shared their political wisdom with Harlemites.”3}

1963 would prove the pivotal year. Yuri goes on:

In October... I saw Malcolm for the first time. That was a turning point for me. Malcolm had come several times to Downstate during the demonstrations. He didn’t participate-he was still under orders from Elijah Muhammed [sic] not to get involved with civil rights activities-but he would be there watching. In the foyer of the courtroom, I asked one of the civil rights leaders I knew if he would introduce me. He said just go over and introduce yourself. Of course, I was a bit afraid to do it, but I went over to where he was talking and stayed a little outside the group; they were all black. He looked over a couple of times and didn’t say anything. Finally, I said I just wanted to let him know how much I admired him. I was really at a loss for words; I wasn’t sure if he would consider me a person of color. He beckoned me to come forward and I put my hand out to shake hands. He looked very stern, and when I said I didn’t know if he would meet with people other than blacks, he said, “Well” - and then he burst into that fantastic smile and put his hands out. The civil rights movement had just come north and I had just got my feet wet. There were lots of things about the black people’s struggle I didn’t understand. I told Malcolm: “I admire you, but there are things I disagreed with.” Okay, he said, you disagree with me; what about? I disagreed with him about integration; I believed in it. He said we can’t in two minutes discuss the pros and cons of integration; come to the Hotel Theresa. That was where his office was; I was awestruck. Then everybody closed in, wanting to get their say, too, and I backed away, and watched as he shook hands and took in, almost penetratingly, each person’s name. I was amazed that he did that because it seemed like he might never see any of these people again.4

The two first met in the Brooklyn courthouse on October 16th because Yuri “and her sixteen-year-old son, Billy [William Earl], were among the more than six hundred arrested during a CORE protest demanding jobs for Black and Puerto Rican construction workers.”5 Malcolm was in attendance in a show of support. On the following evening, Yuri’s “meeting” with Malcolm continued, but this time over the airwaves. She relates:

The following night I heard him on the radio, debating with other black leaders. I thought what he said was so illuminating and forceful, and that he was so unmitigating in his stance, that I sat down at the typewriter and wrote him a letter about the discussion, and about meeting him, and hoping that there might really be the time one day when I could go to his office to discuss some things.6

In Fujino’s biography of Yuri, The Revolutionary Life of Yuri Kochiyama, part of that first letter to Malcolm is reproduced for us:

My son and I just finished listening to the radio broadcast... I could not constrain myself from writing to you... I shall always admire you and respect you for what you are doing for your people - giving them the “lift,” the support, and pride in their heritage. More than that, you are giving much to all of us - penetrating into all the infested areas bloated with pomposity... It may be possible that non-Negroes may wake up and learn to treat all people as human beings. And when that time comes, I am sure that your pronouncement for separation will be changed to integration. If each of us, white, yellow, and what-have-you, can earn our way into your confidence by actual performance, will you... could you... believe in ‘togetherness’ of all people?7

Yuri sent the letter in great anticipation of a response. She describes that period of waiting as follows:

Then every day for weeks, I looked in the mail for an answer. The months went on. Kennedy was killed in November of that year, and Malcolm made the statement about the chickens coming him to roots...8

Yuri would never receive a written response to her letter - Malcolm’s schedule was too busy and his life in too much turmoil to allow him the time to write back - but this did not mark the end of their encounter. Nor did Yuri’s tentative position expressed in her first letter remain fixed for long. She sought deeper answers and would radically develop her outlook in close conversation with Malcolm’s teachings. Indeed, their next meeting would prove potent in many ways - something I plan to explore in the next essay.

Yuri Kochiyama, Passing It On: A Memoir (Los Angeles: UCLA Asian American Studies Center Press, 2004), 76.

Yuri Kochiyama, Fishmerchant’s Daughter: An Oral History, Vol. 2, ed. Arthur Tobier (New York: Community Documentation Workshop, 1982), 1.

https://www.nytimes.com/2000/07/30/nyregion/neighborhood-report-harlem-legendary-bookstore-gets-last-minute-lease-life.html

Kochiyama, Fishmerchant’s Daughter, Vol. 2, 2.

Diane C. Fujino, The Revolutionary Life of Yuri Kochiyama: Heartbeat of Struggle (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2005), 135.

Kochiyama, Fishmerchant’s Daughter, Vol. 2, 2-3.

Fujino, Revolutionary Life, 138-139.

Kochiyama, Fishmerchant’s Daughter, Vol. 2, 3.