Malcolm's Last Moments

Views From Alongside: Benjamin Kareem, Yuri Kochiyama, and Betty Shabazz

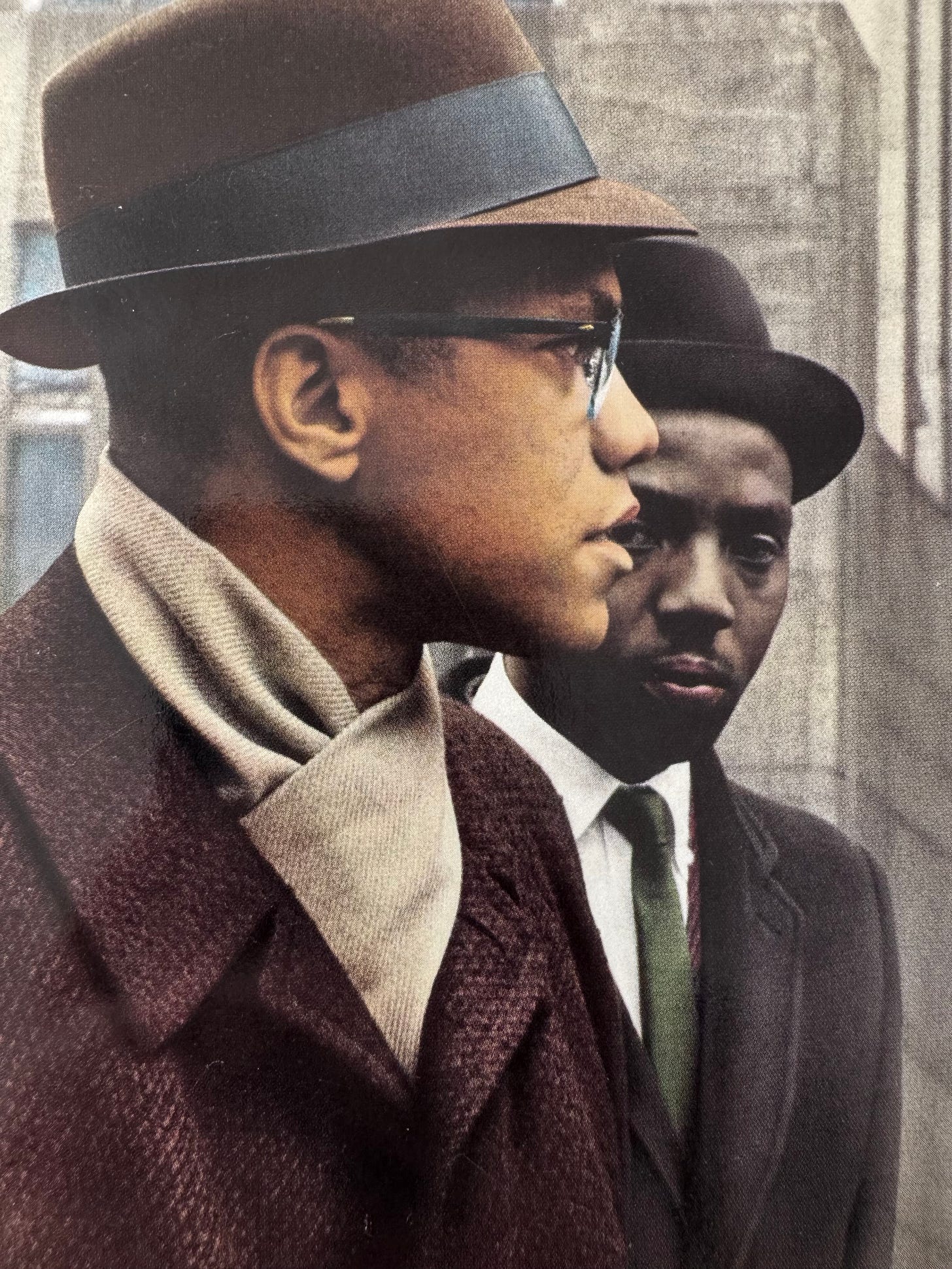

Today marks the sixtieth anniversary of Malcolm X’s transition from this life and this world, the dunyā, to the next, the ākhira. Despite the ever growing distance between then and now, Malcolm’s words, deeds, and commitments continue to resonate for us. He reminds us that righteousness often runs against the grain of our present realities. His struggle, of course, was not waged alone. When Malcolm died, others were by his side. My hope here is to shine a light on some of those other lives who shared those last moments with him - lives that found new depths and trajectories in the wake of his death.

To that end I have gathered here three accounts of Malcolm’s last moments as witnessed and experienced by those drawn into his orbit during his lifetime. The first is Benjamin Karim, who followed Malcolm out of the Nation and towards new horizons. Then, I turn to a life indelibly touched by Malcolm that I’ve been recounting these past few essays - Yuri Kochiyama. Finally, I’ll close with one of the closest to Malcolm, Dr. Betty Shabazz, his wife.

Benjamin Karim

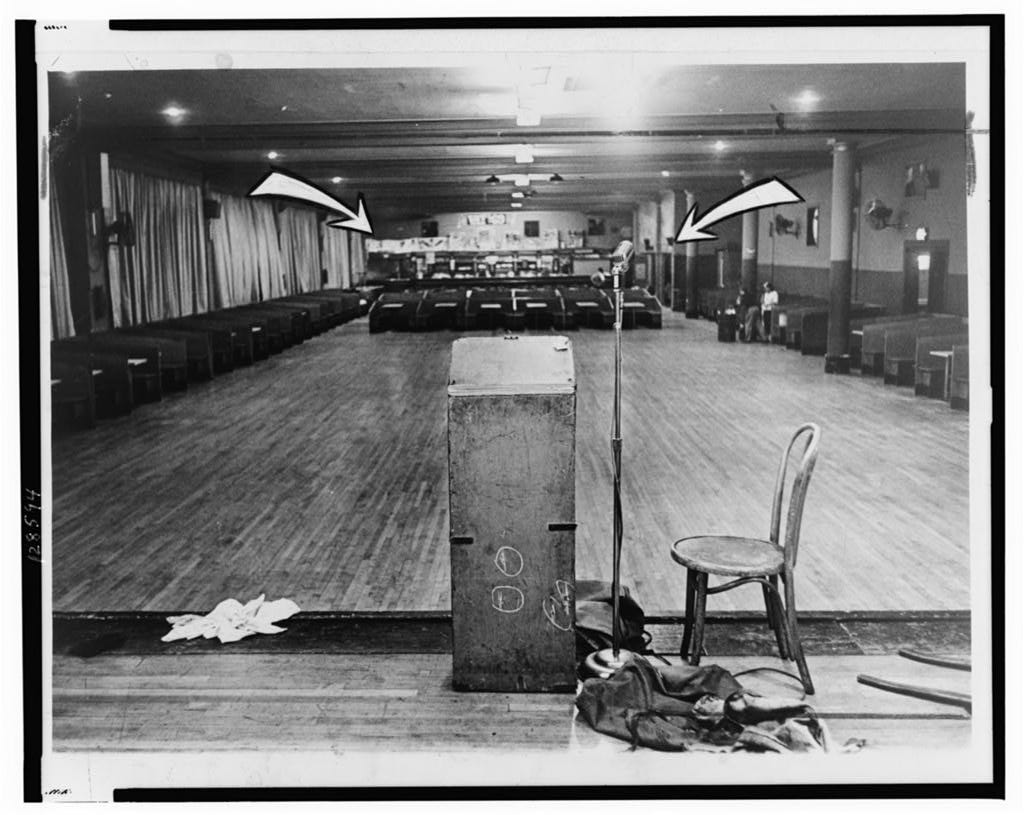

On the afternoon of Malcolm’s last hours, just prior to the gathering that was set to start at 2pm in the Audubon Ballroom, Benjamin was present behind the scenes when Malcolm was informed of a series of disappointments. Two invited guests (Reverend Dr. Galamison & disc jockey Ralph Cooper) and a performing group booked to open the event had all failed to appear. Additionally, the members of the Organization of Afro-American Unity (OAAU) tasked with drafting the OAAU charter had been unable to do so prior to this meeting. According to Benjamin’s account, Malcolm’s reaction was uncharacteristic: Malcolm exploded. He was furious. The end, it must of seemed, was closing in. Just a week earlier Malcolm’s home in East Elmhurst, Queens had been firebombed with his family narrowly escaping. The threats against his life mounted relentlessly. The disarray of this particular OAAU rally proved to be a breaking point. Benjamin Karim recalls:

A sense of terrible foreboding had overcome me backstage at the Audubon. Neither singly nor together could Galamison’s failure to appear or Cooper’s cancellation or the unfinished charter fully explain Malcolm’s behavior. God, we are told, does not burden a soul with more than it can bear, but I had thought as I’d stood there before his fury that Malcolm’s soul could not bear much more. A metaphysical weight, it seemed, was sitting heavily on his back and shoulders. I felt the weight myself, on my shoulders, but I knew it did not lighten the burden for him. I didn’t know, either, what could.1

Malcolm would then ask Benjamin to offer an introduction, which he dutifully did for some 20 to 25 minutes. As he closed, Benjamin offered these final words as Malcolm took the stage, “I present to you... one who is willing to put himself on the line for you... a man who would give his life for you...”2 Benjamin Karim’s own recollections capture the turmoil he was feeling in that tense moment:

When I finished, the weight seemed only heavier on my shoulders, and under my suit I could feel the perspiration rising on my back. I turned away from the podium. I was going to take the stage chair that Malcolm had been sitting in, but he stopped me. He put his hand on my arm and spoke into my ear. He instructed me to go to the green room just offstage and to have Brother James [Shabazz] and the OAAU secretary inform him the minute that Reverend Galamison arrived. Somewhat perplexed - it seemed apparent to me that Galamison would not appear - I left the stage. As I stepped into the green room I felt beads of perspiration beginning to dampen my forehead. I shut the door behind me telling James and the secretary what Malcolm had said. Then I sat down. I heard a sound like firecrackers, I heard panic, I heard blasts of gunfire - all in a matter of seconds. The perspiration broke out of every pore in my body. I knew he was gone.

I knew that he was gone even before the door from the stage to the green room burst open and someone came running through. I just sat there, stunned, staring through the open doorway at the body on the stage. I couldn’t move. Malcolm was lying on the floor of the stage, his face up, and I thought for a moment that he was trying to breathe, but his eyes were fixed - it seemed almost that they were fixed on me - fixed and unblinking; and I couldn’t move. Then, all at once, it left me, the weight on my shoulders, and I felt a great relief come over me, Malcolm’s relief from all his suffering. Death ends a thing on time. Whatever may be the instruments to bring it about, when it comes, it comes on time.3

Yuri Kochiyama

Aspects of Yuri’s account are captured in a number of places: memoir, biographies, and iconic images. Having met Malcolm a year and a half before and eventually having him over as a guest of distinction to her bustling home, Yuri had become a regular at OAAU rallies. This day at the Audubon Ballroom, then, was no different. As Les and Tamara Payne note, “Yuri Kochiyama, a Japanese American human rights activist, took a seat in the third row on the left side with her sixteen-year-old son.”4 This was Billy, her eldest child. Then, according to Marable Manning, Malcolm arrived, “A few minutes after the formal program began at two thirty p.m.… Malcolm showed up, bringing James 67X [James Shabazz], who spoke fluent Japanese, and several security people.”5

Yuri provides a vivid, almost methodical recollection of that day in an interview with her biographer Diane Fujino. Sounding almost like a testimony, she shares:

Now as I recall that date, February twenty-first, 1965, I was sitting in the same booth as Herman Ferguson, which was, I think about the seventh or eighth row. I was with my sixteen-year-old son, Billy, I was taking notes of Brother Benjamin’s [Karim’s] message. He had just finished saying, just before introducing him, ‘Malcolm is a kind of man who would die for you.’ The distraction, a man yelling, ‘Get your hand out of my pocket,’ took place across from where we were sitting. All eyes were turned to the distraction. Malcolm tried to calm the people, saying, ‘Cool it, brothers, cool it.’ Then shots rang out from the front, Malcolm fell straight backward, and it was right then, all hell broke loose. Chairs crashing to the floor. People hitting the floor. People chasing the killers. A few more gunshots, and something like a smoke bomb was thrown. It was utter chaos.

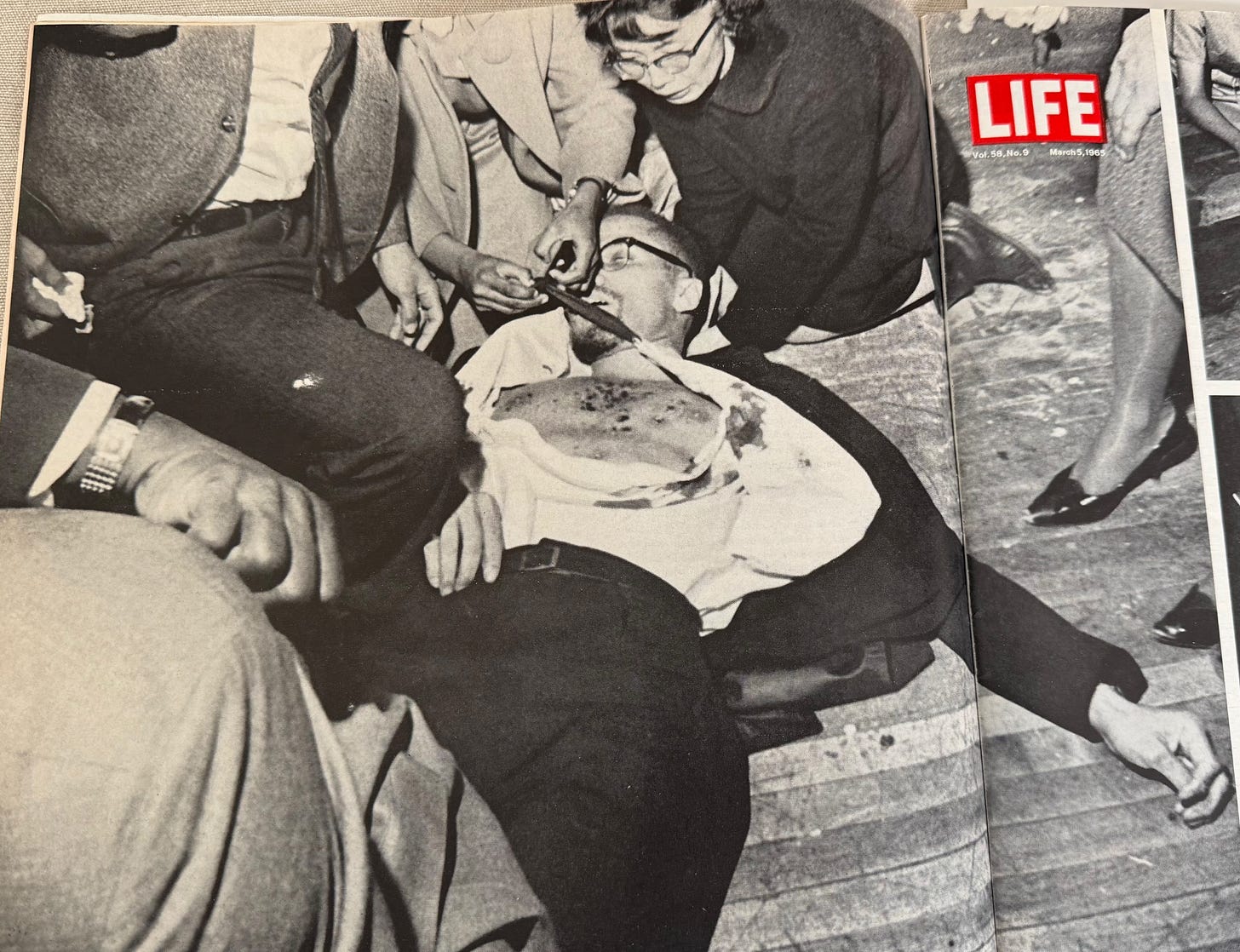

It was then that a young brother... ran past where I was sitting. He was heading for the stage, so I followed him and went right to Malcolm. He was having difficulty breathing, so I put his head on my lap. Others came and opened his shirt. He was shot many times in the chest. And by his jawbone and his finger. I hoped he would say something, but he never said a word.6

Other accounts flesh out the scene further. Payne adds, “Kochiyama made her way to Malcolm, ‘There were only a few of us who were right around him,’ she recalled. ‘For a while I had him cradled… sitting on the floor, I had his head in my lap.’”7 Welton Smith, a reporter for the New York Herald Tribune, was also present. Marable relates, “As several MMI [Moslem Mosque Inc.] security personnel attempted to keep others from crowding onto the stage, Smith saw Yuri Kochiyama, an OAAU member, bend over Malcolm and heard her shout, ‘He’s still alive! His heart’s still beating!’”8

In her memoir, Yuri captures the chaos in her own words. Her succinct, but equally poignant distillation reads:

On February 21, 1965, Malcolm was assassinated while speaking to his OAAU and Muslim Mosque followers at the Audubon Ballroom where he spoke weekly. I was in the audience when Malcolm X was assassinated and immediately ran on stage as soon as he fell to the floor. Cradling his head in my hands, I was shocked. Only one of his killers was apprehended. Two others were arrested, but there was controversy over their arrest. His sudden death was devastating for Harlem, for other Black communities, and for the Black liberation movement. However, the movement could not be extinguished. The movement continued doggedly but also in spurts. New faces, younger and more militant, filled the gap of the struggle. The movement mushroomed and became more radical.9

While much focus has been placed on the immediacy of that tragic moment, more happened in the aftermath in the Audubon Ballroom. The Dead Are Rising paints a fuller picture, which also introduces us to our last witness to Malcolm X’s final moments, Betty. The biography reconstructs the scene as follows:

Betty Shabazz wandered dazed through the Audubon hall, while a small knot of women friends and strangers milled about her fallen husband. One of the women passed Malcolm’s youngest daughter, along with her baby bottle, to Yuri Kochiyama, who had been sitting with Betty. ‘They looked so frightened,’ said Kochiyama, a spirited woman who had once hosted Malcolm at a meeting of Japanese writers at her Harlem apartment. Once someone else relieved her of her nursing duties, Kochiyama, with her hesitant yet determined will for order, asked a woman standing nearby to comfort Sister Betty and keep her and the children back from the wounded Malcolm, who was still lying on the floor”10

Betty Shabazz

For Dr. Betty Shabazz, that primary source that I am drawing from is the biography written by Russell Rickford, Betty Shabazz: A Remarkable Story of Survival and Faith Before and After Malcolm X. Starting much earlier in the day, Rickford retraces Betty’s journey into Harlem and ultimately the Audubon Ballroom. He writes:

Malcolm telephoned Betty at nine in the morning on February 21, 1965, and asked if it would not be too much trouble for her to collect the girls and ferry them to the Audubon for the two o’clock lecture. “Of course it won’t!” Betty said. The request surprised her. Earlier he had forbidden her to attend, insisting that the scene was too risky. Why the change of heart? Betty would never know whether he had had a premonition. “But it was a very warm conversation,” she later remembered. Before the minister hung up, he told her that someone - it had sounded like a white man - had phoned his hotel room an hour earlier and said, “Wake up, brother.” Betty and the girls were late arriving at the Audubon. She had spent the early afternoon encasing them in snowsuits and preparing for the drive to Manhattan, pin-curling her hair and sheathing her hands and forearms in long black gloves. The children were fidgety. A trek uptown was a departure from the tenor of recent days. “It was still an exciting adventure to get ready and go see Daddy,” Attallah (then six) later remembered. By the time Betty marched the girls up to the second-floor ballroom, the flecks of sunlight that had stolen into the musty room were starting to skitter back out. It was shortly before 3 P.M. (Malcolm had been checking for her in the audience and had asked someone to call the Wallaces to see if she had left.) The four hundred seats were filling fast... Betty steered her daughters up one of two side aisles, past the rows of wooden chairs in the center of the room and the restaurant-style booths along the walls. She ushered the girls into the second booth near the stage (on Malcolm’s left as he took the podium) and started peeling off their snowsuits. “We were seated near the front on one side of those old-fashioned benches with a drop front - it was like a box with a back,” she later recalled.”11

Then, Rickford works to place us at the scene of the assassination but from Betty’s point of view:

Betty heard the blast of a shotgun and swiveled back toward the stage. “I knew there was no one else in there they’d be shooting at,” she later remembered. She heard someone say, “Oh my God, on my God,” and she saw Malcolm stiffen, his hands flying up halfway, his face and white dress shirt speckled with blood. Then there was the clak! clak! of pistols and his eyes were rolling back, his mouth dropping open... Betty saw him keel over and crash through the chairs behind him. She heard the thud as his head slammed into the dusty stage... and then she was snatching her children, sweeping them to the floor beneath the booth’s wooden bench, shielding them with her body and coat... Betty lay there atop her daughters with her head bowed. She held them down to protect them as much as to calm them; the assassins might have wanted the wife and daughters, too. But the gunmen were busy guaranteeing their hit. They stood before the sprawled minister and squeezed shot after shot into his jerking body, the bullets sizzling into his calves and thighs. “They’re killing my husband!” Betty heard herself scream.12

Then, our biographer continues:

The place erupted. Everybody was screaming, colliding, ducking, skidding, hurdling chairs, and dashing for the exit. Beneath Betty, one of the Shabazz girls wailed that she could not breathe. “Are they going to kill everyone?” another daughter sobbed.13

Finally, Rickford writes:

Betty, who had been frantically wheeling about somewhere in the eddy of overturned chairs, now sliced through the clot of onlookers. She was hysterical. A woman grabbed and slapped her. “He can’t see you like this!” she said. Finally the ring of aides parted. Still sobbing, Betty knelt by her husband and knew instantly that he was gone. She had wanted to perform mouth-to-mouth resuscitation, but now started on CPR. Then she seized his hands and pumped his arms uselessly, her face a mask of anguish... Somebody pulled Betty off of her husband and led her into the wings. “Oh, Muriel,” she said to Feelings, “he’s gone! And I’m *pregnant*!” Feelings glanced down from the stage and saw Attallah’s tiny, crimson face burst into a shriek that still ricochets in both women’s hearts. A dozen or more policemen finally sauntered into the dance hall. Yuri Kochiyama, who had cradled Malcolm’s head in her lap while the others tried to revive him, drifted over to the stage’s side door. Someone thrust seven-month-old Gamilah into her hands and she stood there numbly, feeding the infant milk from a bottle. The women had ushered the other Shabazz girls into the green room. Betty now drew the terrified and confused children near. “Suddenly I feel too old to be sitting on that lady’s lap,” Attallah later recalled.14

This terrible day in the ballroom was not the first meeting between Yuri Kochiyama and Betty Shabazz. In the months leading up to February 1965, the two of them had been gradually getting better acquainted with one another. The biography of Dr. Betty Shabazz records:

Earlier that summer [of 1964], [Betty] had managed a couple of unescorted visits to the home of Japanese-American Yuri Kochiyama, a Harlem activist who had met and befriended Malcolm in late 1963. “She wasn’t afraid to walk the streets,” Kochiyama later remembered. Betty had perched at the edges of Kochiama’s [sic] multicultural affairs, enjoying polite conversation and talking proudly about her children while other guests hovered respectfully. “Everybody’s talking to her because it’s their one opportunity,” Kochiama [sic] recalled.15

Their growing connection did not end with Malcolm’s death either. Several days after his demise Yuri sent her condolences to Betty offering words that I think serve as an appropriate ending. Rickford records:

Among the early epistles was a February 25, 1965 telegram from Harlem human-rights activist Yuri Kochiyama. “No words can express the profound grief that we share with you,” Kochiyama wrote. Malcolm was more than one great man, she declared. He was “an epic.” She closed with a wish for endurance: “May his great love for you and your children and your infinite love for him keep his spirit alive forever.”16

Benjamin Karim with Peter Skutches & David Gallen, Remembering Malcolm: The story of Malcolm X from inside the Muslim mosque by his assistant minister Benjamin Karim (New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, Inc., 1992), 188-189.

Russell J. Rickford, Betty Shabazz: A Remarkable Story of Survival and Faith Before and After Malcolm X (Naperville: Sourcebooks, Inc., 2003), 228.

Karim, Remembering Malcolm, 190.

Les Payne and Tamara Payne, The Dead Are Rising: The Life of Malcolm X (New York: Liveright Publishing Company, 2020), 473.

Manning Marable, Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention (New York: Viking, 2011), 340.

Diane C. Fujino, The Revolutionary Life of Yuri Kochiyama: Heartbeat of Struggle (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2005), 159.

Payne & Payne, The Dead Are Rising, 484.

Marable, Malcolm X, 439.

Yuri Kochiyama, Passing It On: A Memoir (Los Angeles: UCLA Asian American Studies Center Press, 2004), 72.

Payne & Payne, The Dead Are Rising, 483-484.

Rickford, Betty Shabazz, 226-227.

Rickford, Betty Shabazz, 229.

Rickford, Betty Shabazz, 230.

Rickford, Betty Shabazz, 231.

Rickford, Betty Shabazz, 206.

Rickford, Betty Shabazz, 292.

Thank you for this, which is so poignant for our times, especially for aspiring ethical Muslims. Ramadan Mubarak! :)