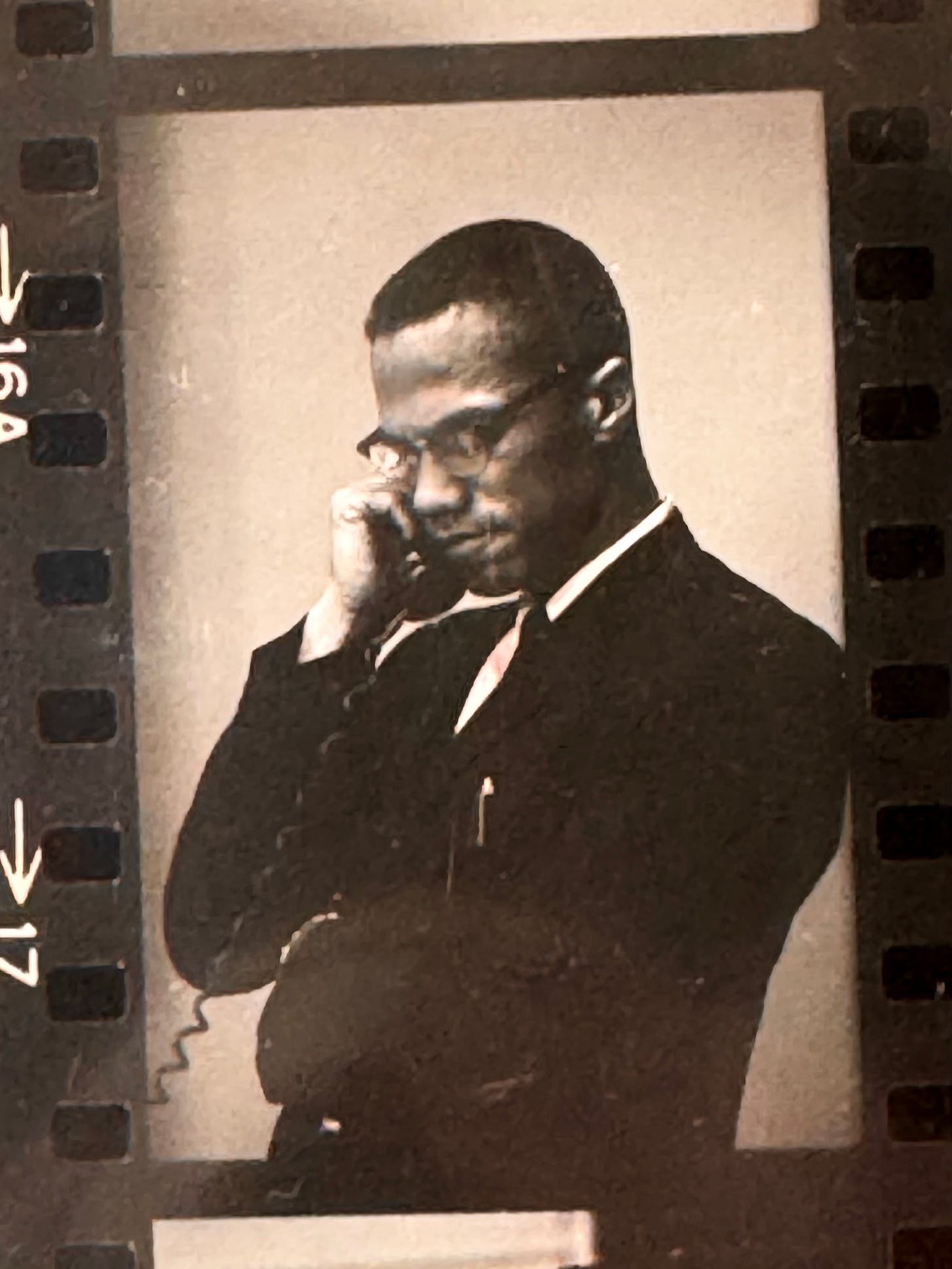

It is hard to deny that a certain poetry underlies and animates Malcolm X’s life as well as his words. There is a noticeable way that he resonates and reverberates for us many years later. Yet, when it comes to poetry proper, few references to it emerge with respect to his biography. Yet in my recent work on Malcolm X, I’ve come across what I would call some of the poetry that he bore - poems that he carried with him one way or another. I want to share, then, two such poems that helped to form and inform him.

The first poem is one that has received some attention in Malcolm X-related scholarship. During his last full year of life in 1964, Malcolm travelled widely to parts of Europe, Africa, and the Muslim world. He kept a travel diary spanning from April 15 to May 21, 1964 and then from July 10 to November 17, 1964. Malcolm’s daughter Ilyasah Al-Shabazz and Herb Boyd have since edited the travelogue publishing it back in 2013.1 Earlier this year, I visited the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in order to take a closer look at this important document in the Malcolm X collection. I was especially interested in a poem that was first documented, as far as I can ascertain, by Maytha Alhassen in her dissertation “To Tell What the Eye Beholds: A Post 1945 Transnational History of Afro-Arab ‘Solidarity Politics,’” and then referenced again by Hamzah Baig in his article “‘Spirit in Opposition:’ Malcolm X and the Question of Palestine.”2

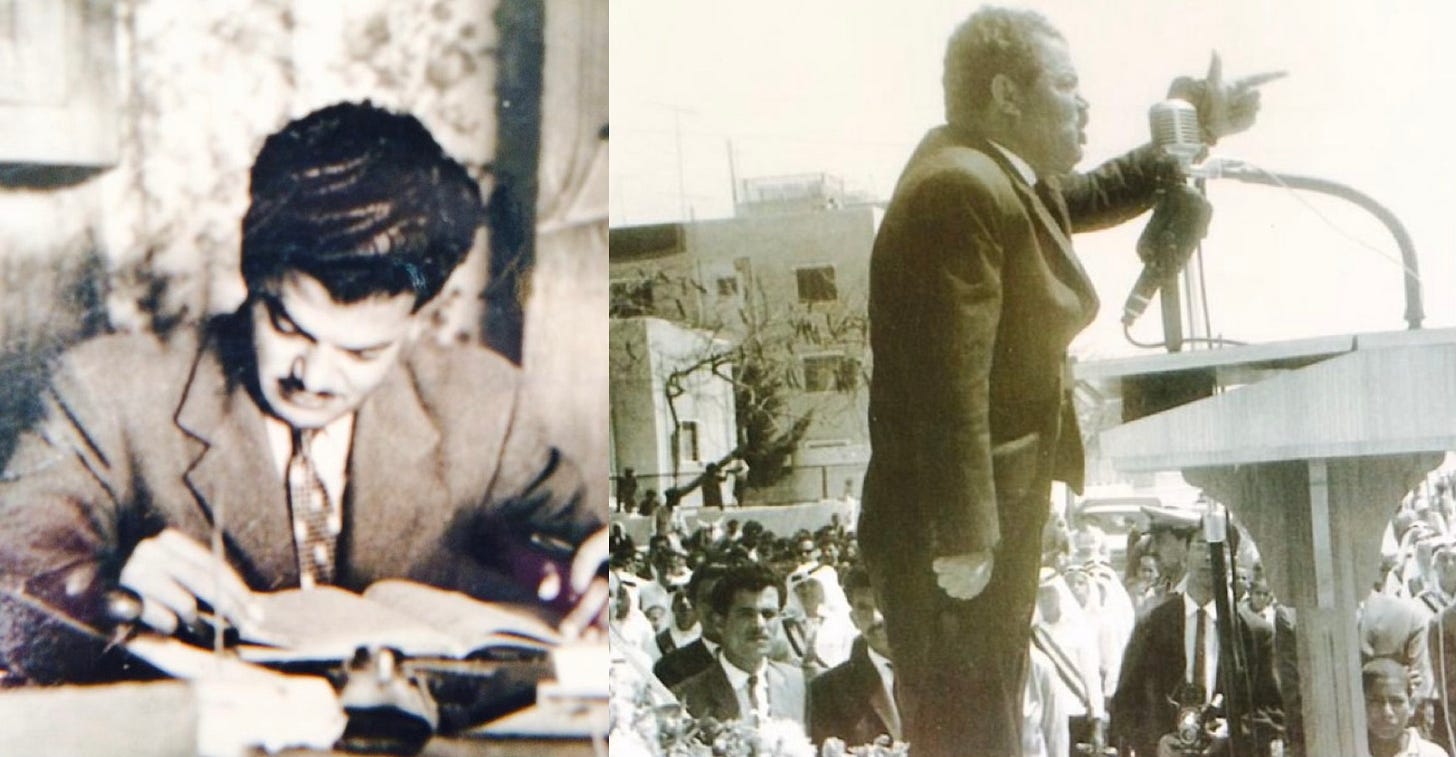

According to the record of his life, during Malcolm’s visit to Egypt he traveled to Gaza spending two days there from Saturday morning, September 5th to the noon of the following day, Sunday, September 6th. Reflecting on that first day, he wrote “The spirit of Allah was strong.”3 He also spent some time with Palestinian poet Harun Hashim Rashid. Malcolm relates in his diary, “Then we napped until 6 pm. Harum Hashid Rashid [sic] sat telling me of his many experiences & escapes when Israel invaded Gaza in ‘56. At 8:25 pm we left for the mosque to pray…”4 More specifically, Rashid related to Malcolm his escape from the November 3, 1956 Khan Younis massacre eight years prior.

In addition to this account, of which Malcolm captures some cursory notes in his diary, he also copies down a poem from Rashid. Perhaps because of its placement, it never appears in the published edition of the diary. Specifically, Malcolm writes the poem down on the pages following the final formal entry in his diary, the one for November 17, 1964. Alhassen believes it is a version of a poem that Rashid published in 1960 entitled Ḥattā yaʿūd shaʿbūnā or “Until Our People Return,”though it might not have been published in a book collection until 1966.5 Upon discovering this poem, I wanted to see the poem for myself in Malcolm’s own hand. After examining it in the archives, I believe the poem was transcribed faithfully except for a minor error. In the sixth verse, the version reproduced by Alhassen and Baig contains the word “alley,” where I believe the microfiche of Malcolm’s diary actually reads “valley.”6 The poem he transcribes reads:

We must return

No boundaries should exist

No obstacles can stop us

Cry out refugees: “We shall return”

Tell the Mts: “We shall return”

Tell the valley: “We shall return”

We are going back to our youth

Palestine calls us to arm ourselves

And we are armed and are going to fight

We must return

Recited to him in Gaza by its author, Malcolm was so moved by the piece that he felt compelled to record it down in his hasty hand near the back of his travelogue. He did not want to forget it. Its verses clearly struck a chord. That chord continues to reverberate across time to our present - “We shall return.”

As for the second poem, I learned of it during my research on Yuri Kochiyama, rather than Malcolm. There are signficant ties, of course, connecting the two of them, which I have tried to document in a few recent pieces. While reading Diane Fujino’s biography of Yuri, I came across the following unexpected reference to Malcolm and the poetic. Discussing Yuri’s love of poetry from an early age, Fujino reports of Yuri that:

She was surprised to discover decades later that one of her favorite poems, Rudyard Kipling’s “If,” was one Malcolm X carried in his pocket, a gift given to him by his sister, Ella Collins.7

That a poem by English novelist and poet Rudyard Kipling (1865-1936), whose work reflects and refracts so much of the “might” of the British Empire, might seem a surprising choice for Malcolm, especially given that more infamous poem of Kipling’s “The White Man’s Burden” (1899) and Malcolm’s own fierce anti-colonialism.8 Yet, the meaningfulness of the selection might have as much to do with who gifted it to Malcolm, his half-sister Ella Collins, as the content of the poem itself. Ella played a pivotal role in Malcolm’s life, by first bringing him out to Boston during his late teenage years, then supporting him (eventually) during his time with the Nation of Islam, and finally waiting for him after his tumultous departure from it. Malcolm recalls, “she was the first really proud black woman I had ever seen in my life… I had never been so impressed with anybody.”9 As Malcolm shares later in the Autobiography, it was Ella who provided the funds necessary for him to undertake the Hajj pilgrimage at that critical time in 1964.10

This poem, then, is not simply a poem by Kipling, but a poem bequeathed to Malcolm by an enduring supporter and a beloved sister. It proved a poem significant enough for Malcolm to keep close by upon his person, a fact that he would eventually share with his friend Yuri Kochiyama some time later. Indeed, it was a poem that Muhammad Ali would also carry upon him.11 That poem, “If,” reads:

If you can keep your head when all about you

Are losing theirs and blaming it on you;

If you can trust yourself when all men doubt you,

But make allowance for their doubting too;

If you can wait and not be tired by waiting,

Or, being lied about, don’t deal in lies,

Or, being hated, don’t give way to hating,

And yet don’t look too good, nor talk too wise;If you can dream—and not make dreams your master;

If you can think—and not make thoughts your aim;

If you can meet with triumph and disaster

And treat those two impostors just the same;

If you can bear to hear the truth you’ve spoken

Twisted by knaves to make a trap for fools,

Or watch the things you gave your life to broken,

And stoop and build ’em up with wornout tools;If you can make one heap of all your winnings

And risk it on one turn of pitch-and-toss,

And lose, and start again at your beginnings

And never breathe a word about your loss;

If you can force your heart and nerve and sinew

To serve your turn long after they are gone,

And so hold on when there is nothing in you

Except the Will which says to them: “Hold on”;If you can talk with crowds and keep your virtue,

Or walk with kings—nor lose the common touch;

If neither foes nor loving friends can hurt you;

If all men count with you, but none too much;

If you can fill the unforgiving minute

With sixty seconds’ worth of distance run—

Yours is the Earth and everything that’s in it,

And—which is more—you’ll be a Man, my son!-Rudyard Kipling

Here are verses that express Ella’s faith in her younger brother. Here are words conveying resilience and endurance in the face of seemingly insurmountable odds. Here are lines to kindle hope and thread difficulties. Here is a poem that inspired Malcolm to continue on in the struggle with which he was so deeply and intimately engaged. It is a poem, we might imagine, that Malcolm could have had on him up until his last moments. Although that carefully carried page of poetry seems all but lost, it remains nonetheless a poem passed from one generation to the next - from Ella to Malcolm, from Malcolm to us.

Malcolm X, The Diary of Malcolm X: El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz, 1964, edited by Herb Boyd and Ilyasah Al-Shabazz (Chicago: Third World Press, 2013).

maytha Maha Yassine Ziad alhassen, “To Tell What the Eye Beholds:

A Post 1945 Transnational History of Afro-Arab ‘Solidarity Politics,’” (Ph.D. dissertation, University of Southern California, December 2017), 203-205; Hamzah Baig, “‘Spirit in Opposition:’ Malcolm X and the Question of Palestine,” Social Text vol. 37, no. 3 (September 2019), 61.

Malcolm X, The Diary of Malcolm X, 115.

Malcolm X, The Diary of Malcolm X, 115.

alhassen, “To Tell What the Eye Beholds,” pp. 203-205. Notably, the WorldCat catalog entry for the poetry collection bearing this title indicates that the first edition of this work was published in 1966, which would have been after Malcolm X’s visit. This might help explain the differences between Malcolm’s recorded version and the published version.

The Malcolm X collection: papers (Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library, Archives and Manuscripts), reel 9, Travel Diary July-November 1965.

Diane C. Fujino, The Revolutionary Life of Yuri Kochiyama: Heartbeat of Struggle (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2005), 27.

See for instance Sohail Daulatzai, Black Star, Crescent Moon: The Muslim International and Black Freedom beyond America (Minneapolis: The University of Minnesota Press, 2013); Russell Rickford, “Malcolm X and Anti-Imperialist Thought,” Black Perspectives: African American Intellectual History Society (24 February 2017), https://www.aaihs.org/malcolm-x-and-anti-imperialist-thought/.

Malcolm X & Alex Haley, The Autobiography of Malcolm X (New York: Grove Press, Inc., 1965), 33.

Malcolm X & Alex Haley, The Autobiography of Malcolm X (New York: Grove Press, Inc., 1965), 321-322.

Tony U. Francisco, “The Poem That Drove Muhammad Ali to Greatness,” Medium (12 March 2023), https://medium.com/hpxl/the-poem-that-drove-muhammad-ali-to-greatness-a5d287b6bc07.

Highly elucidating, as literature held dear to heart often represents the best of our intentions, and a place from which our actions spring forth.

Beautiful piece Prof., I wasn't aware of the Kipling poem and the deep resonance that it had with Malcolm. I"m pretty sure you would've seen it, but in case you haven't, I came across an article that was published a few months back that presented a poem of Malcolm's, plus the Persian poetry that he read in prison:

https://newlinesmag.com/essays/a-new-discovery-sheds-light-on-malcolm-xs-journey-to-islam/